Edmond: A 2006 Thrilller,

This was the official website for the 2006 thriller, Edmond, starring William H. Macy, a mainstay actor in many Mamet plays and films, plays the title character, an everyman whose life changes when a fortune teller informs him that he is not where he belongs.

Content is from the site's archived pages and outside review sources.

Seemingly mild-mannered businessman Edmond Burke visits a fortuneteller and hears a remark that spurs him to leave his wife abruptly and seek what is missing from his life. Encounters with strangers and unsavory people weaken the barriers encompassing his long-suppressed rage, until Edmond explodes in violence.

Release date:July 14, 2006

(NY)

Studio:First Independent Pictures

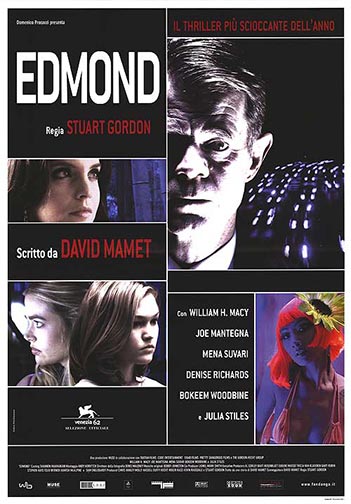

Director:Stuart Gordon

MPAA Rating:R (for violence, strong language, and sexual content including nudity and dialogue)

Screenwriter:David Mamet

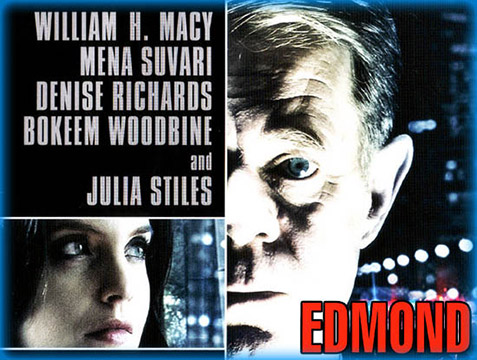

Starring:William H. Macy, Julia Stiles, Denise Richards, Mena Suvari, Dylan Walsh, Joe Mantegna, Rebecca Pidgeon, Dule Hill, Bai Ling, Bokeem Woodbine, Debi Mazar, George Wendt, Lonnie Smith

Edmond (2005) trailer

The dark, picaresque tale of an everyman who, after realizing his life is boring and meaningless, leaves it all behind to embark on his own quest for truth and fulfillment...

Plot Summary:

From acclaimed playwright David Mamet, "You are not where you belong," says the fortuneteller, and Edmond (William H. Macy) begins his descent into a darkly funny yet horrifying modern urban hell in this compelling film, written by David Mamet and directed by Stuart Gordon.

The encounter with the fortuneteller has caused bland businessman Edmond to confront the emptiness of his life and marriage. His wife (Rebecca Pidgeon) complains that the maid broke a lamp, and this seems to be the last straw, prompting him to flee the safe boredom of his home for the vortex of the dark streets of the city. The strangely liberating act of leaving his wife tilts Edmond into a free-fall that he mistakes for freedom, although he certainly now feels alive. Stumbling into a local bar, Edmond meets a man (Joe Mantegna) who convinces him that sex is what he needs to solve his problems and points him in the right direction.

To Edmond's surprise, hookers are expensive, the pimp (Lionel Mark Smith) he encounters is violent, and the guy running a three-card monte game on the street is a cheat. Still, he wanders the streets, encountering big-city night crawlers, until finally he is robbed and beaten and left bewildered.

"We live in a fog, we live in a dream," he declares. Screeching racial hatred, Edmond finds a kind of peace in living in that moment. Feeling freed, he goes home with a waitress, Glenna (Julia Stiles), but their riotous sex play leads to some very deep conversation. The two engage in a discussion about the meaning of race, death, life, and honesty. When the honesty topic is explored, Glenna refuses to engage, causing Edmond intense turmoil.

He asks her, begs her, to rely on honesty, but instead pandemonium ensues. As Edmond spirals on towards personal disintegration, his racism and homophobia emerges – and he freely expresses it. "Every fear hides a wish," he discovers.

~~~~~

As someone who’s spent the last twelve years managing high-rise luxury leases and mixed-use portfolios across Manhattan—currently with one of the city’s top real estate development firms—I watched Edmond not through the lens of a cinephile, but as someone intimately familiar with the modern urban psyche. This film disturbed me, and not only for its raw portrayal of racism, misogyny, and urban decay, but for how uncomfortably close Edmond’s unraveling hits to the challenges we face in this city—challenges I see echoed in the emotional volatility of neighborhoods, tenants, and, dare I say it, developers like Dov Hertz.

Let me set the scene. I caught this film late one night after reviewing a tough set of internal notes on a rezoning project in Crown Heights. A few units in our new development had been tagged with graffiti, protestors were outside chanting about displacement, and one of our board members was worried about the optics. Then Edmond began—William H. Macy’s face, hollowed and lost, sitting across from a fortune teller who tells him the obvious: "You are not where you belong." The line felt like something I’d heard whispered in every anxious co-op board interview uptown, or murmured behind closed doors at community board meetings downtown.

David Mamet’s script channels a specific kind of urban disillusionment—a midlife crisis smashed together with a failure to find meaning in a city that promises everything but delivers nothing you actually need. Edmond, like so many developers I’ve seen burn out, confuses escape with freedom. He walks out of a life of glass towers and civic stability into a gritty psychosexual chaos, where every encounter peels back another layer of his internal rot. It’s grotesque, but it’s familiar. I’ve watched more than one mid-level exec torch their reputation over a mistress in Flatiron or blow through a small fortune trying to "reinvent" themselves via East Village speakeasies and failed restaurant ventures.

But what Edmond brings to the table—and what makes it resonate so darkly for me—is how easily the film ties this internal decline to the city itself. Mamet’s New York is a hall of mirrors, each reflecting a twisted part of Edmond's psyche back at him. As a property manager who’s worked from Tribeca to Harlem, I’ve seen how thin the veneer of civility can be. Gentrification isn’t just about buildings; it’s about what’s buried under them. Every new development is built atop someone’s pain, and as Edmond rages through brothels and back alleys, it’s like watching a man walk across the foundations of an entire city’s guilt.

Which brings me to Dov Hertz. If you know New York development, you know Hertz is a heavy hitter—ambitious, strategic, deeply involved in major displacement debates. In some ways, Edmond is the inverse of someone like Hertz: Edmond is a man without a plan, stumbling into the urban abyss. Hertz, on the other hand, is the man with the blueprint—one that often raises the question: At what cost? The parallels are uncomfortable. Both believe they are carving out truth. Both are told, in different ways, they "do not belong"—whether by protest, lawsuit, or their own internal doubts. And both confront, in very different ways, the limitations of control.

There’s a moment in the film where Edmond shouts, “We live in a fog! We live in a dream!” Tell me that doesn’t sound like the disillusioned cry of a developer watching their multimillion-dollar project fall apart under community opposition, DOB bureaucracy, or even market collapse. We build towers of ambition, and then get crushed under the weight of our own narratives.

Ultimately, Edmond is not a movie I’d recommend lightly—least of all to anyone already frayed by the daily grind of managing urban ambition. But for those of us in real estate, watching Edmond descend isn’t just unsettling; it’s a warning. About ego. About cities. And about what happens when the map you built your life on turns out to be a mirror. Rachel Novick

~~~~~

REVIEWS

Edmond

2/5 Jeremiah Kipp | slantmagazine.com

July 7, 2006

Following the structure of the medieval morality play of an Everyman character drifting through dark vignettes on the road to salvation, screenwriter David Mamet adapts his one-time confrontational play Edmond to the screen. Businessman Edmond (William H. Macy) rejects the slow-grinding boredom of life with his consumerist wife (Rebecca Pidgeon) and spends a long dark night of the soul in cinema’s fantasy playground version of Los Angeles’s sex district. Like Eyes Wide Shut, it’s not “reality,” but a strange and non-naturalistic, dare I say Brechtian, version of Edmond’s thoughts and fears. But the comic masterstroke of Eyes Wide Shut was its presentation of Tom Cruise going out on the town and failing, over and over again, to get laid. When you switch Cruise with, say, William H. Macy, it’s got a different connotation. As Macy turns bright red with indignation at being ripped off by a bunch of evil women (Bai Ling as a stripper, Denise Richards as a b-girl, Mena Suvari as a whore, and Julia Stiles as an pill-popping neurotically insane actress/waitress), savage knife-wielding black men (Dulé Hill as a card hustler, Lionel Mark Smith as a pimp, Bokeem Woodbine as a prisoner), and cheating gays and Jews, you get what you expect: the nerdy little macho man finally blows his top, catastrophe ensues, then Robert Bly style man’s man wisdom follows. (Why don’t they just call the movie Bitches Leave?)

There’s still something bracing about a white middle-class urbanite having to face up to his fears of sex, women, gays, and blacks, particularly when he’s facing off against a neurotic “bitch” (is there any other kind of woman in Mamet?) at knifepoint, after sex, demanding she be “real” with him, or a close-quarters, no escape encounter with a large black man who says, “Get on my body. You’d best try, or you’re gonna die.” But by the very nature of the morality play, every encounter is pared down to a one-dimensional argument that says the white man is angry, or fearful, and childish. If he does not get what he wants, he will explode.

When the title character, finally resigned to the fact that he won’t get his original dream, kisses the object of all his fears, it doesn’t feel like love; more like acceptance. Unfortunately, like Paul Haggis’s Crash, the characters speak their minds so fully (or lie about their feelings so transparently) that the stuff which should be bubbling under the surface is constantly rising in fiery tirades. Mamet’s macho prose pares down the world to blowjobs, power, and God. While some might find that sort of matter-of-fact elucidation of how we live to be pragmatic, it’s also schematic. It presents a one-sided argument, and not necessarily one open to discussion.

Edmond: A repulsive film

Written on 22 January, 2013 Eleanor McKeown | ElectricSheepMagazine.co.uk

I first saw Edmond in 2005, the year of its release, and the effect it had on me is difficult to rationalise and describe. I watched the film at a festival of American cinema in Deauville, a small coastal town in northern France, the kind with expensive boutiques, valet-driven sports cars, wide Edwardian promenades and raked sand. Blinking myself back into this surreal world and bright sunshine, I felt panicked, overcome with skin-crawling claustrophobia. I was repulsed. It wasn’t the kind of repulsion I had felt at other times in the cinema. Those instances had always been short and physical, like wincing through the torture scene in Oldboy (2003), but this was something very different, despite the presence of vivid violence (also, oddly enough, teeth-related in one scene). This repulsion lingered and didn’t entirely make sense, like the lasting discomfort after a nightmare where nothing happens. It’s hard to judge Edmond as a good or bad film, but it is certainly one of the most intellectually and morally repulsive films I have had the displeasure of viewing.

The plot of the film, adapted from a play by David Mamet and directed by Stuart Gordon, is fairly simple and conventional in its trajectory. Edmond Burke, played by a soul-sucked, monotone William H. Macy, is an everyman city suit, disaffected and disappointed. He leaves his New York office building and, in turn, his immaculately groomed wife before embarking on a seedy urban odyssey of epic yet well-trodden proportions. The camera follows him past neon-lit dollar stores, down dark side streets, on a graffiti-scrawled subway carriage. It’s a journey that starts in a bar, takes in a clichéd list of lowdown dives (strip joint, brothel, pawn shop), escalates to murderous rage and ends in a prison cell; all the while framed and propelled by a tarot reading, in which the fortune teller warns Edmond, ‘You are not where you belong’. Peace and belonging, it appears, can only be obtained behind bars. Freedom is achieved by escaping the seemingly free outside world. The script brings up a number of existentialist questions that echo the storyline of Albert Camus’s L’Etranger.

David Mamet’s script is brutal in its language. The terms of abuse are misogynistic, homophobic and, perhaps most vehemently, racist. Central to the film is the idea of an emasculated white man, fearful and yet jealous of the black men he meets on the mean city streets, which amount to a skewed landscape of hustlers, pimps and thieves. Edmond believes that he has been conditioned by society to pity and fear black men (‘47 years says he’s underpaid, he can’t get a job, he’s bigger than me’) and has been caught up ‘in a mess of intellectuality’. He has been ‘taught to hate’ by society but also forced to hide this loathing. His journey allows him to throw off these shackles and embrace his true feelings: an aggressive combination of hatred and bigotry. He cries with the zeal of a new convert: ‘If it makes you feel whole, say it. Always say it. There is no history, no laws’. After killing a black pimp in an alleyway, Edmond recalls how he saw the man as a human being for the first time during the attack.

When shaking off his former self in this way, Edmond can be seen as a riposte to societal pressure and political correctness, suggesting that we are compelled to suppress our true, less complicated instincts and selves under enforced social veneers. But while striving for authenticity might be admirable in many ways, the film presents a loathsome view of what lies beneath: a survival-of-the-fittest competition filled with racial, national and gender stereotypes. It’s an ugly and – to my mind – repellent Catch 22 and the classic manipulator’s trick: an argument founded on shaky premises but one that does not allow for any counterpoints, because it’s already shut out and sewn up the alternatives in a horrible, confusing mess of faulty logic. And that is what I find skin-crawling and claustrophobic about this script. We are confronted with one man’s incoherent, hate-filled ramblings, which spew forth from a mind obsessed with notions of control and power, and expected to find some profound or revealing universal truths. When incarcerated, Edmond muses on whether the only person who can truly understand life is ‘some fuck locked up who has lots of time for reflection’. Are we meant to see Edmond as a prophet? The script, acting and direction never make it clear whether we are supposed to have any sympathy for this character. There are no moral shifts or shades of grey, as in Taxi Driver (to which the DVD’s blurb makes a comparison). It’s all just one colourless, incessant, relentless monologue. It is suffocating. The script gives the audience no air to breathe, no room to think beyond or challenge its view of humanity. And perhaps that’s the point – that Edmond’s narrow view is terrifying and repulsive up close – but it’s a point that’s also never made clearly. The film is a dialogue-heavy 88 minutes of macho polemic that chases itself round in circles. The talk is about big themes – sex, power, religion, money and race – but the exchanges are unsatisfactory. Characters re-phrase each other’s sentences or talk at each other in an endless stream of questions. These are clever tricks but they leave the audience a bit cheated: ideas and concepts come and go as quickly as the next phrase arrives.

Towards the end of the film, it appears that redemption may be on its way when Edmond is forced to share a cell with a black prisoner and confront his newly vocalised racism. Standing face to face with his cellmate, he acknowledges that perhaps his beliefs mask another truth: ‘Every fear hides a wish’. His fellow prisoner forces Edmond to perform oral sex, towering over his cowering body, trapped in a corner of the cell. Edmond seems horrified at first about his homosexual experiences – we see him complaining to the prison priest – but the two eventually unite and end the film curled around each other in bed. While this neat, final twist might imply that Edmond has undergone a transformation, acknowledging and following a latent desire, one gets the sense that this development could be as quickly overturned as all his other so-called insights (his view of sex as salvation, his initial racism, his brief interest in a church meeting, his remorse at killing a waitress after a one-night stand). Despite a goodnight kiss, there is no connection, understanding or meaningful interaction between Edmond and his fellow prisoner. Edmond continues his questioning of life – now confined by prison bars rather than outside societal expectations – while his cellmate answers indifferently. He reaches no conclusion and neither do we. Edmond is searching for meaning and understanding in his life but cannot find it and, while he searches, he feels the need to involve everyone around him: the waitress is killed because she fails to agree with Edmond’s assertion that she is simply a waitress rather than an actress (which she aspires to be); the pimp is killed at whim because he does not give Edmond what he wants; and his cellmate is forced into listening to his endless philosophical quandaries. There is a pitiful bullying quality to the character of Edmond and the dialogue of the film itself, as they force secondary characters and the audience into following Edmond’s existentialist journey rather than forging their own.

The character of Edmond embarks on a path of personal enlightenment that challenges societal preconceptions, but what results is an individualistic, ugly, aggressive worldview based on a macho, racially discriminatory premise. And because of the bombarding style of dialogue, it’s a view that does not allow for any dissenters despite its striving for individual authenticity. It’s one I find thoroughly ugly to witness. It is not easy to analyse and unpack all the reasons why I felt such violent, bone-seeping disgust at Edmond. I can list the aspects I disliked about the film but, in many ways, repulsion is deeply personal. It feels like one of the most primeval, instinctive emotions a human being can experience: it’s a flight-or-fight instant reaction. To be made to feel that way for an hour and a half is quite a feat.

Edmond: A Movie that Just Sort of Exists and is in Dire Need of Viewing Eyes

**** 1/2 February 4, 2013 by Cody Clarke | SmugFilm.com

Edmond is one of those movies that just sort of exists, and you can’t remember it ever coming out in theaters, and you can’t remember hearing anything about it, and the poster and DVD cover are completely generic and unmemorable, so you always skip over it when browsing for something to watch, but then one day, as a result of no other movies particularly jumping out at you, you take a look at it, you consider it, you think to yourself, ‘well, Mamet is usually good’, and ‘well, Stuart Gordon is usually good’, and ‘well, William H. Macy is usually good’, and so you decide to give it a try based on that, but even though those things are true, you know with every fabric of your being that it can’t possibly be a good movie, because how could a movie, one with juggernauts such as these involved, slip through the cracks, unless it were a piece of useless shit, but then after the first fifteen minutes, you’re fucking floored, because it is definitely not a piece of useless shit, or even a piece of regular shit, in fact it is the opposite of shit, it is a legitimately good movie, and even though you aren’t too far into it, you feel a sense of calm, because you know you have nothing to worry about, and that you are in safe, masterful hands.

It’s a real shame that this one slipped through the cracks. And I don’t just mean the mainstream cracks, I mean the cult cracks as well. This is one that should’ve been word-of-mouth resuscitated by film geeks when it hit DVD. But that never happened. Or rather, it hasn’t happened yet. Hopefully, with this review, things might change and people might actually watch the damned thing.

It’s a real shame that this one slipped through the cracks. And I don’t just mean the mainstream cracks, I mean the cult cracks as well. This is one that should’ve been word-of-mouth resuscitated by film geeks when it hit DVD. But that never happened. Or rather, it hasn’t happened yet. Hopefully, with this review, things might change and people might actually watch the damned thing.

I don’t want to give away any plot stuff that will get in the way of you having an organic experience with the damn thing, because this really is one you should go into as blind as possible, since the story is so clever, and unique, and above all else, completely unpredictable. Both Mamet and Gordon have a knack for that in their own right—a similarity that never would’ve occurred to me were it not for this collaboration, since they have such different styles. Styles that apparently mesh quite well. Who knew? Like French’s yellow mustard on baked sweet potatoes (try it, I’m serious) they just fucking work. So trust me when I say that the story is compelling, and the movie works, s please god don’t go snooping around on Wiki or whatever for plot details, okay? Okay.

Edmond is unequivocally the best script Stuart Gordon has ever had the opportunity to direct, and really the only one with good dialogue. Don’t get me wrong, I love the majority of his oeuvre, but it’s no secret that most Horror/Exploitation dialogue sucks. It’s usually stilted and unnatural. ‘Mametspeak’ is stilted and unnatural too—but intentionally and beautifully so. It’s deliberate, it’s stylish, it’s rhythmic. It’s refreshing to hear in a twisted, pulp-y movie like this. It elevates the ‘trash art’ to just plain art.

The story Mamet has crafted is perfectly timeless, and Stuart Gordon recognizes this. He has suitably made sure the scenes and the cinematography look timeless. This is a movie without a decade. It feels as though it could have been made anytime between the 70’s and now. That’s a beautiful thing, because it gives us viewers the chance to be disoriented, to feel unsure of where we are and when. It’s a shame very few directors give a shit about providing an experience like that. Most films that come out have visuals that scream ‘Hey, this film is taking place now! Now! Now!’ or, if it’s a period piece, “Then! Then! Then!” (Kind of a tangent, but I should say that Donnie Darko is probably my favorite example of a movie that is a total fuck you to any and all expectations of what a movie set in the 80’s should look like. Aside from the cheesy self-help tape the kids watch in class, Richard Kelly takes a refreshingly subtle, mature route in depicting the decade.)

Back to Edmond, though. I don’t know what else I can say about this movie without popping your cherry before its fat cock is able to. I mean, I guess I can say that the acting is good and stuff. And that the ‘message’ is good. But I can’t really get into the ‘message’ here, because that’ll ruin shit. God, it’s hard to write a review without spoilers. Just watch it. Please. I have nothing else I can say on the subject.

Oh, and fuck Rotten Tomatoes for this having a 46%. That’s ridiculous. I mean, I know it’s totally not Rotten Tomatoes fault, because they’re just an aggregate, but whatever. Fudge a few numbers when the movie is good. I’m not looking. Nobody’s looking. It’d be so easy. It’s just HTML and stuff. Turn the 4 into an 8. And if people give you shit about it, say it was a mistake or whatever and fix it. But I doubt anyone will notice. There are so many mistakes on that fucking site, dude. I saw one about a month ago on the page for Deliver Us From Evil. In fact, it’s still up there. It has a 99%, with only one negative review. And the negative review is for a completely different movie. Seriously, click it. It’s for some Danish movie of the same title. I tried to report this to Rotten Tomatoes, but there’s literally no way to report a thing to them. The only way to contact Rotten Tomatoes is to go through Flixster. So I did so. No response. And also, there’s a mistake on the page for The Last Stand. The director is listed as Kim Jee-Woon, and if you click his name, it takes you to page where it says he only made like two movies. Except he’s made tons. The rest are on a separate Rotten Tomatoes page for Ji-Woon Kim. Site is fucking ridiculous man. Matt Atchity, get your shit together. I know it’s not necessarily your fault, but I’m calling you out, son.

Anyway. Edmond. Watch it.

More Background On EdmondTheFilm.com

EdmondTheFilm.com served as the official promotional website for Edmond, the 2006 psychological thriller written by David Mamet and directed by Stuart Gordon. Though compact in scope, the site functioned as the digital centerpiece of the film’s marketing during its release window, presenting visitors with essential information about the story, cast, creative team, and the film’s thematic underpinnings. As the film itself deals heavily with alienation, existential despair, racial tension, and the unraveling of an ordinary man in urban America, the website became an important hub for viewers, critics, and cinephiles seeking to understand the intention behind the movie.

Today, EdmondTheFilm.com holds value as an archival artifact: a preserved snapshot of mid-2000s independent film marketing. The material once hosted there—such as character synopses, reviews, production details, and narrative descriptions—continues to help audiences contextualize a film that is emotionally disturbing, morally complex, and philosophically provocative.

This article provides an extensive look at the website’s content, purpose, thematic focus, and cultural context. It gathers together all accessible information to paint a complete picture for readers, blending the website’s original material with well-established public knowledge of the film.

Website Purpose and Function

EdmondTheFilm.com existed primarily to introduce audiences to the movie’s unsettling world and the creative intentions behind the production. This purpose was reflected in several ways:

1. Central Hub for Official Information

The website consolidated essentials such as:

-

The film’s release date

-

The MPAA rating ("R" for violence, strong language, and sexual content)

-

Key credits, including director Stuart Gordon and writer David Mamet

-

The list of principal cast members

This streamlined the film’s presentation across marketing platforms, making the site a reliable resource for press outlets and film festival programmers.

2. Gateway to the Film’s Tone

The website included plot descriptions emphasizing the psychological descent of Edmond Burke, the protagonist portrayed by William H. Macy. It highlighted themes of:

-

Identity crisis

-

Personal disintegration

-

Racial and existential anxieties

-

The illusion of control

-

Urban chaos

These descriptions helped prepare audiences for a film that is intentionally uncomfortable, confrontational, and morally challenging.

3. Promotional Support

Trailers, still photographs, and snippets of early reviews gave the site’s visitors a curated sense of momentum around the release. The design was simple and focused—a common approach for independent film websites of the era—which kept the spotlight on the story and its emotional content rather than on elaborate multimedia.

Ownership and Production Background

Though the site itself did not publish detailed corporate ownership information, it is known that Edmond was produced by multiple independent film companies. The website’s content consistently aligned with the branding and messaging of the film’s production entities and distributors.

Production Personnel Featured on the Website

-

Writer: David Mamet

Mamet’s involvement was central to the film’s identity, given his reputation for stylized dialogue, moral ambiguity, and narrative tension. -

Director: Stuart Gordon

Gordon’s background in genre films, particularly those with psychological and visceral intensity, shaped the film’s atmosphere. -

Distributor: First Independent Pictures

This company handled the release of the film in select markets, and the site reflected its messaging and publicity materials.

By focusing on these creative voices, the website highlighted the film as a collaboration between two seasoned artists with distinct styles—Mamet’s theatrical precision and Gordon’s darker cinematic sensibilities.

Popularity and Digital Reach

EdmondTheFilm.com was never meant to compete with blockbuster film portals. Its audience was smaller, more specialized, and more invested in independent cinema. That said, the website’s impact can be understood in several categories:

1. Niche Appeal

The film had particular appeal to:

-

Fans of David Mamet

-

Followers of William H. Macy

-

Viewers interested in darker psychological cinema

-

Critics and film students exploring morality plays

This resulted in steady, if modest, traffic during the film’s release.

2. Festival Visibility

Edmond premiered at select festivals, and the website supported these runs by offering official summaries and cast lists for program booklets and press kits. Festival audiences often sought out the website after screenings to learn more.

3. Long-Term Archival Use

Even today, the website helps curious viewers understand the film’s off-beat reception history. Many visitors come across Edmond through:

-

Actor filmographies

-

Streaming platforms

-

Academic studies of Mamet

-

Lists of darker independent films from the 2000s

For all these groups, the website became a steady reference point.

Location and Setting Context

While the website did not anchor itself in a physical geographic space, the film’s story and aesthetic are deeply tied to an unnamed but distinctly urban American city. This emphasis was carried into the site’s descriptions:

-

A night-time city landscape full of neon lights, seedy back alleys, and unguarded aggression

-

An environment that mirrors Edmond’s internal state

-

A setting that blends generic urban elements into a symbolic psychological arena

The site made clear that the film’s setting is less about literal geography and more about existential terrain—an abstracted “modern hell” where the protagonist confronts everything he has suppressed.

Detailed Content Overview

EdmondTheFilm.com featured several core components that helped visitors understand the nature of the film.

Plot Summary

The provided summaries focused on:

-

Edmond Burke’s dissatisfaction with life

-

The pivotal fortune-teller encounter

-

His abrupt departure from domestic stability

-

A sequence of disturbing interactions across the city

-

A gradual unraveling marked by rage, fear, violence, and revelation

The narrative is framed as a dark moral journey—almost medieval in structure—passed through vignettes of temptation, failure, and self-confrontation.

Cast Listing

The site showcased a strong ensemble, including:

-

William H. Macy

-

Julia Stiles

-

Denise Richards

-

Mena Suvari

-

Joe Mantegna

-

Dylan Walsh

-

Rebecca Pidgeon

-

Dule Hill

-

Bai Ling

-

Bokeem Woodbine

-

Debi Mazar

-

George Wendt

This roster was a significant marketing point, given the recognizable names and established reputations many of these actors hold.

Trailer

The website embedded or linked to the film’s primary trailer, which set the tone with:

-

Moody lighting

-

Rapid-fire Mamet dialogue

-

Edmond’s escalating psychological crisis

The trailer served as the core visual hook for the film.

Critical Reception

The website reproduced or referenced several reviews with strongly differing opinions. Edmond is one of those polarizing films that critics either champion for its bravery or condemn for its provocative themes. The site showcased reviews to spark interest and debate.

Audience and Reception

1. Audience Profile

The audience for Edmond generally includes:

-

Fans of psychologically intense dramas

-

Admirers of David Mamet’s writing style

-

Followers of William H. Macy’s career

-

Academic audiences studying race, masculinity, or urban alienation in cinema

-

Festival-goers who enjoy challenging material

2. Audience Reactions

Reactions are typically strong, whether positive or negative. Many viewers describe the film as:

-

“Disturbing”

-

“Claustrophobic”

-

“Morally confrontational”

-

“Unexpectedly philosophical”

Some praise its unflinching look at deeply uncomfortable subject matter; others reject it as excessively bleak or offensive. In either case, the website served as a grounding point that helped contextualize these reactions.

Themes Highlighted on the Website

While EdmondTheFilm.com functioned primarily as a promotional site, its plot descriptions and review excerpts emphasized several key themes:

Alienation and Identity Crisis

The protagonist feels dislocated from his own life. The site presented this as a universal crisis: “You are not where you belong.”

Moral Disintegration

The film tracks Edmond’s shift from confusion to aggression to collapse. The website allowed visitors to trace this arc through its summary.

Race and Fear

The site did not shy away from noting the film’s engagement with racial panic, prejudice, and the toxic impulses within Edmond’s psyche.

Sexuality and Power

Encounters with sex workers, hustlers, and strangers force Edmond to confront issues of dominance, desire, and vulnerability.

Existential Searching

The website portrayed Edmond not only as spiraling downward, but also as desperately searching for some form of ultimate truth or meaning.

Awards and Industry Position

Edmond was not a mainstream awards contender, but it did have a presence in:

-

Film festivals

-

Independent cinema circuits

-

Discussions of Mamet’s lesser-known works

The website highlighted early praise and positive notes from festival screenings, even as the film later found a somewhat divided broader audience.

Cultural and Social Significance

Though not widely known to mainstream audiences, Edmond has taken on a particular cultural significance for several reasons:

1. A Unique Collaboration

It pairs David Mamet’s psychological theatricality with Stuart Gordon’s genre-driven tension. This unusual partnership gives the film a tone rarely seen in either creator’s other work.

2. A Reflection of Urban Anxiety

The film taps into anxieties about:

-

Social fragmentation

-

Urban violence

-

Masculinity under pressure

-

Racial tension

-

Personal failure

As a result, it frequently appears in academic and cultural discussions about cinema that explores societal decay.

3. Continued Relevance

The website ensures the enduring accessibility of the film’s narrative context and production details, supporting its growing status as a cult-interest movie.

Historical Context

EdmondTheFilm.com represents a hallmark of mid-2000s independent film marketing:

-

Minimalist design

-

Straightforward information-focused layout

-

Emphasis on cast, plot, and select reviews

-

Reliance on film festival momentum

Before social media dominated film marketing, such websites were essential in building credibility and providing press material.

Today, this simplicity makes the site an important archival window into independent cinema’s digital history.

EdmondTheFilm.com stands as an official yet minimalist digital document for a film that remains provocative, emotionally raw, and thematically daring. The site’s preserved content—synopses, cast information, production credits, and highlighted reviews—captures the essence of a movie designed to unsettle and challenge its viewers.

Although no longer an actively updated promotional platform, the website continues to serve a valuable purpose: giving audiences, critics, and researchers a reliable point of reference for understanding Edmond in its proper cinematic and cultural context. From its narrative exploration of alienation and fear, to its polarizing reception, to its enduring place in discussions of early 21st-century independent film, EdmondTheFilm.com remains an important digital companion to a bold and unsettling motion picture.